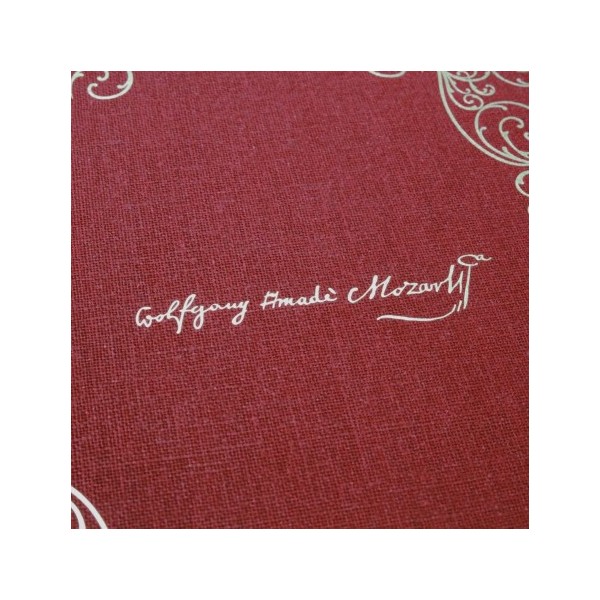

Mozart's Musical Diary by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Large format (10 x 14'')

Mozart’s Musical Diary

Mozart’s last musical diary, entitled Verzeichnüss aller meiner Werke, or Catalogue of my works, is a vivid testimony of the virtuoso composer’s work produced during the golden age of his career — the last decade of his life. Mozart used this diary to organize and catalogue all the compositions that he worked on and completed during the seven years that preceded his death, between 1784 and 1791. He meticulously wrote in and maintained the notebook until a few weeks before his sudden and tragic death in 1791.

An overview of Mozart's creative genius

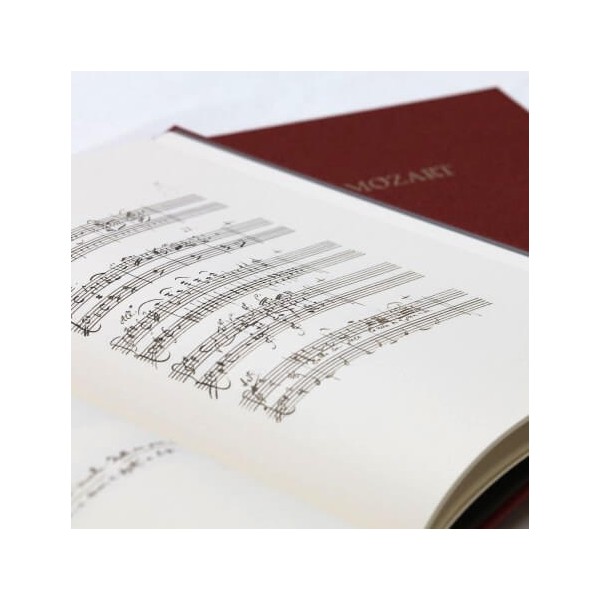

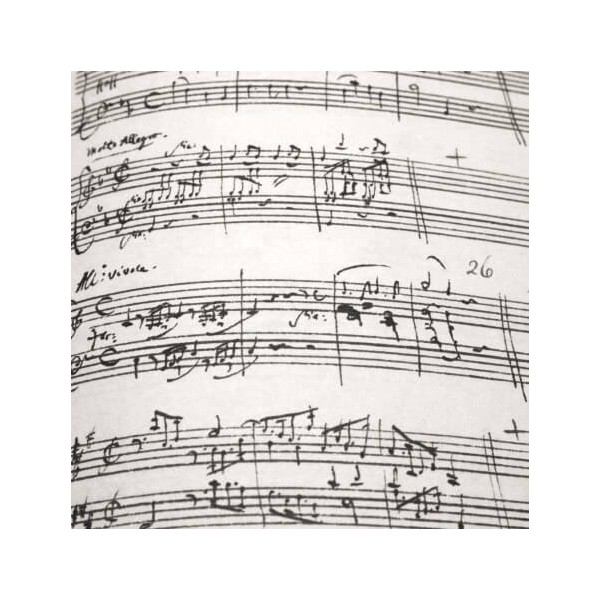

The notebook presents to the reader extracts from Mozart’s rich and varied corpus, in his own handwriting. Entries include major masterpieces like The Magic Flute, The Marriage of Figaro, Eine kleine nachtmusik, quartets written for his friend Haydn, as well as many of his more minor works such as his “musical joke” (Ein musikalischer Spass), pieces for beginners, piano variations, sonatas and arias... The pieces represented in this notebook also vary in form and in length: entries include compositions scored for voice, chamber orchestras and string instruments, piano alone, duets, as well as operas, concertos, cantatas etc. The scores as written out in these notebooks sometimes vary from the form in which we know them today, or the official notation —Mozart often reworked his partitions, famously changing details in his compositions up until the very last minute.

Of particular interest among these entries are several “lost compositions”: compositions that have otherwise been lost and for which no other traces subsist. There also exists gaps in this catalogue: entries of known works that are left out here, but referenced for instance in the Köchelverzeichnis (the 19th century chronological catalogue of Mozart’s compositions, realized by the Austrian musicologist Ludwig von Köchel). Exactly why Mozart left out certain compositions remains somewhat of a mystery today — did Mozart deem them not important enough to be included? Or perhaps never truly finished?

It is also worth noting that Mozart only entered completed works, which explains why the notebook holds no mention to his most acclaimed (but famously unfinished) work — his Requiem in D minor.

The manuscript of Mozart's life's work

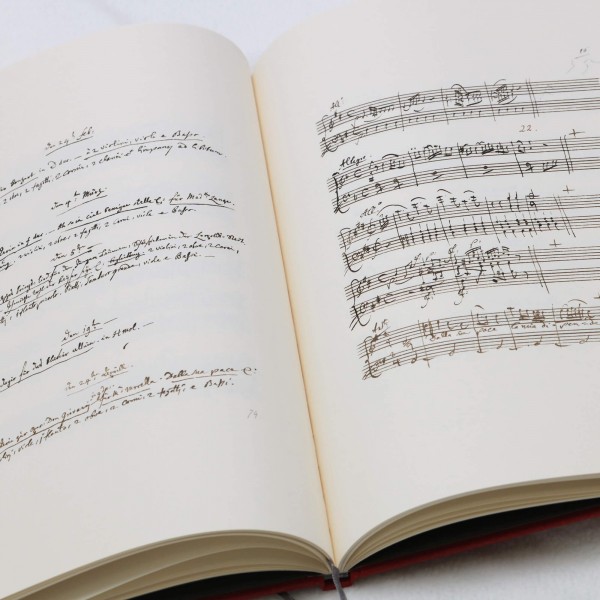

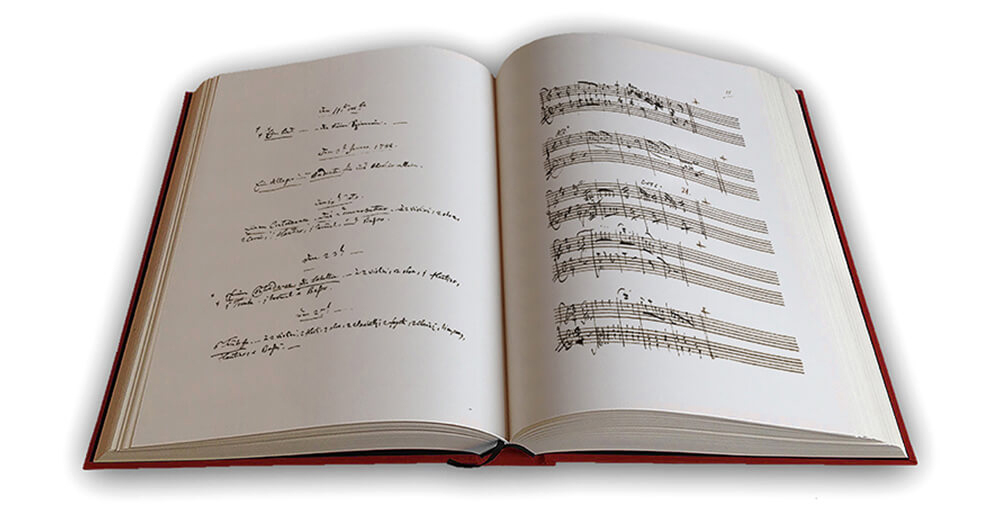

This thematic catalogue, or musical diary, is composed of a total of 48 leaves: 44 leaves with entries, and 4 leaves left blank after his sudden death in December 1791. Mozart wrote across the open notebook, from left to right: each page-spread contains five entries and each entry is spread across the left and right-hand pages.

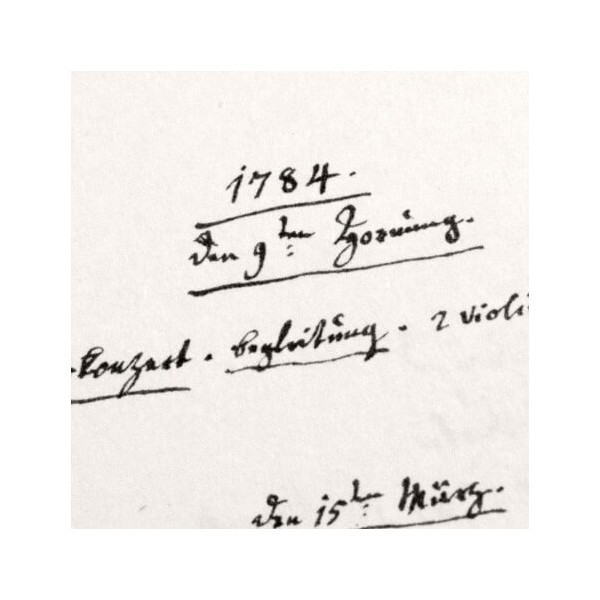

On the right–hand page of each spread, he entered the first two staves of the catalogued work’s musical notation. And on the left-hand page of the notebook, Mozart inscribed the corresponding date, title, and instrumentation. He also occasionally listed other details such as where the work was composed or performed, the names of the singers that a given piece was scored for, or the person who commissioned the work.

Mozart often composed pieces for specific singers — he liked to think of himself as a tailor, composing for voices: music that would best match certain individuals. In the catalogue we see him compose works for sopranos Aloysia Lange, Louise Villeneuve, and Caterina Cavalieri, and baritone Luigi Bassi (the first to play Don Giovanni at the 29 October 1787 Prague opening) among others.

The reader will see that there are some small symbols and notes that probably weren’t written by Mozart, but more likely by Mozart’s widow, Constanze, her second husband (who wrote Mozart’s biography), or the musical publisher Johann Anton André.

The document’s story

We know from her correspondence that Mozart’s widow, Constanze, was fully aware of this document’s significance. For a period after his death, she guarded the document zealously, and refused to relinquish or share it. She eventually acquiesced and sent it to the musical publisher Johann André (whose father Mozart knew well) at the turn of the 19th century. André eventually, towards the end of his life, attempted to sell his Mozart archives but was unsuccessful. The documents were inherited by his six sons and one son-in-law, and in 1935 the catalogue was sold in an auction to Austrian writer Stefan Zweig. In 1956 the Zweig family deposited it to the British Museum on loan, and it was later acquired by the British Library in 1986.

The manuscript “gives us an immediate and illuminating insight into Mozart’s miraculous productivity, and, through the features of his handwriting, into facets of his enigmatic personality.” Albi Rosenthal — “The history of Mozart’s thematic catalogue – or Mozart’s musical diary.”

Deluxe edition

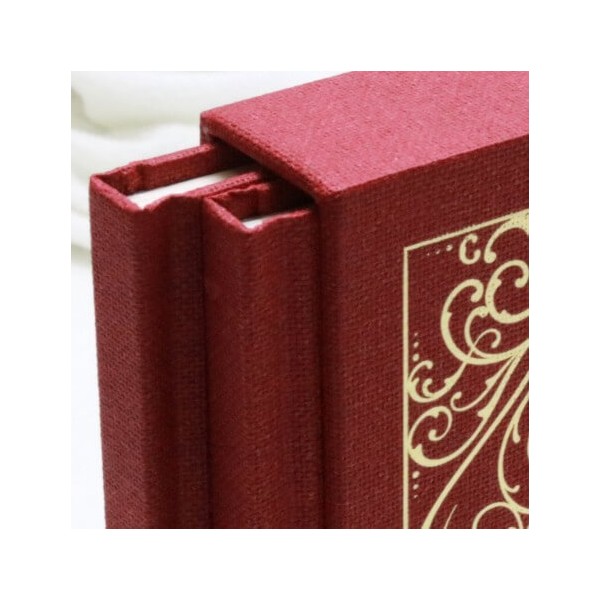

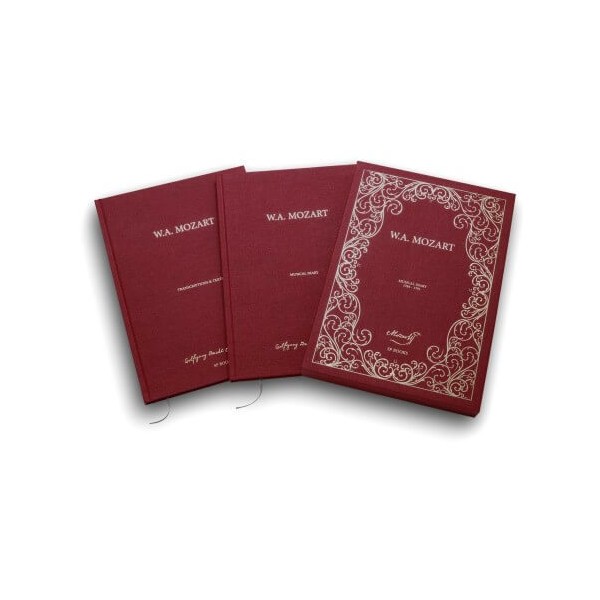

This is a two-volume trilingual edition (English, French and German). Volume 1 is a reproduction of the musical diary and volume 2 is a transcription of the document’s text complemented by two explanatory texts written by two Mozart specialists, Albi Rosenthal, and Alan Tyson respectively.

Deluxe edition

Numbered from 1 to 1,000, this Carmine red edition is presented in a large format handmade slipcase.

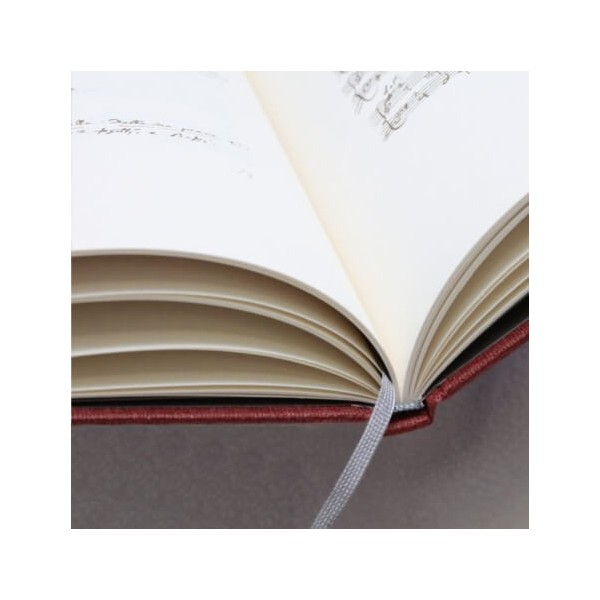

Printed with vegetal ink on eco-friendly paper, each book is bound and sewn using only the finest materials.

Mrs Dalloway: Thanks to a new reproduction of the only full draft of Mrs. Dalloway, handwritten in three notebooks and initially titled “The Hours,” we now know that the story she completed — about a day in the life of a London housewife planning a dinner party — was a far cry from the one she’d set out to write (...)

The Grapes of Wrath: The handwritten manuscript of John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath, complete with the swearwords excised from the published novel and revealing the urgency with which the author wrote, is to be published for the first time. There are scarcely any crossings-out or rewrites in the manuscript, although the original shows how publisher Viking Press edited out Steinbeck’s dozen uses of the word “fuck”, in an attempt to make the novel less controversial. (...)

Jane Eyre: This is a book for passionate people who are willing to discover Jane Eyre and Charlotte Brontë's work in a new way. Brontë's prose is clear, with only occasional modifications. She sometimes strikes out words, proposes others, circles a sentence she doesn't like and replaces it with another carefully crafted option. (...)

The Jungle Book: Some 173 sheets bearing Kipling’s elegant handwriting, and about a dozen drawings in black ink, offer insights into his creative process. The drawings were not published because they are unfinished, essentially works in progress. (...)

The Lost World: SP Books has published a new edition of The Lost World, Conan Doyle’s 1912 landmark adventure story. It reproduces Conan Doyle’s original manuscript for the first time, and includes a foreword by Jon Lellenberg: "It was very exciting to see, page by page, the creation of Conan Doyle’s story. To see the mind of the man as he wrote it". Among Conan Doyle’s archive, Lellenberg made an extraordinary discovery – a stash of photographs of the writer and his friends dressed as characters from the novel, with Conan Doyle taking the part of its combustible hero, Professor Challenger. (...)

Frankenstein: There is understandably a burst of activity surrounding the book’s 200th anniversary. The original, 1818 edition has been reissued, as paperback by Penguin Classics. There’s a beautifully illustrated hardcover, “The New Annotated Frankenstein” (Liveright) and a spectacular limited edition luxury facsimile by SP Books of the original manuscript in Shelley's own handwriting based on her notebooks. (...)

The Great Gatsby: But what if you require a big sumptuous volume to place under the tree? You won’t find anything more breathtaking than SP Books ’s facsimile of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s handwritten manuscript of The Great Gatsby, showing the deletions, emendations and reworked passages that eventually produced an American masterpiece (...)

Oliver Twist: In the first ever facsimile edition of the manuscript SP Books celebrates this iconic tale, revealing largely unseen edits that shed new light on the narrative of the story and on Dickens’s personality. Heavy lines blocking out text are intermixed with painterly arabesque annotations, while some characters' names are changed, including Oliver’s aunt Rose who was originally called Emily. The manuscript also provides insight into how Dickens censored his text, evident in the repeated attempts to curb his tendency towards over-emphasis and the use of violent language, particularly in moderating Bill Sikes’s brutality to Nancy. (...)

Peter Pan: It is the manuscript of the latter, one of the jewels of the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library, which is reproduced here for the first time. Peter’s adventures in Neverland, described in Barrie’s small neat handwriting, are brought to life by the evocative color plates with which the artist Gwynedd Hudson decorated one of the last editions to be published in Barrie’s lifetime. (...)